James Abbott McNeill Whistler Biography In Details

Early Life

James Abbott McNeill Whistler was born in Lowell, Massachusetts. He was the first child born to George Washington Whistler, a prominent engineer, and Anna Matilda McNeill (his father's second wife). At the Ruskin trial (see below), Whistler claimed the more exotic St. Petersburg, Russia as his birthplace: "I shall be born when and where I want, and I do not choose to be born in Lowell," he declared. In later years, he would play up his mother's connection to Southern and Scottish roots, and present himself as an impoverished Southern aristocrat (although to what extent he truly sympathized with the Southern cause during the American Civil War remains unclear).

Young Whistler was a moody child prone to fits of temper and insolence, who after bouts of ill-health often drifted into periods of laziness. His parents discovered in his early youth that drawing often settled him down and helped focus his attention.

Russia and England

Beginning in 1842, his father was employed to work on a railroad in Russia. After moving to St. Petersburg to join his father a year later, the young Whistler took private art lessons, then enrolled in the Imperial Academy of Fine Arts at age 11. The young artist followed the traditional curriculum of drawing from plaster casts and occasional live models, reveled in the atmosphere of art talk with older peers, and pleased his parents with a first-class mark in anatomy. In 1844, he met the noted Scottish artist Sir William Allan, who came to Russia with a commission to paint a history of the life of Peter the Great. Whistler's mother noted in her diary, "the great artist remarked to me 'Your little boy has uncommon genius, but do not urge him beyond his inclination.'"

In 1847-8, his family spent some time in London with relatives, while his father stayed in Russia. Whistler's brother-in-law Francis Haden, a physician who was also a talented artist, spurred his interest in art and photography. Haden took Whistler to visit collectors and to lectures, and gave him a watercolor set with instruction. Whistler was already imagining an art career. He began to collect books on art and he studied other artists' technique. When his portrait was painted by Sir William Boxall in 1848, the young Whistler exclaimed that the portrait was "very much like me and a very fine picture. Mr. Boxall is a beautiful colourist. It is a beautiful creamy surface, and looks so rich." In his blossoming enthusiasm for art, at fifteen, he informed his father by letter of his future direction, "I hope, dear father, you will not object to my choice." His father, however, died from cholera at the age of forty-nine, and the Whistler family moved back to his mother's hometown of Pomfret, Connecticut. His art plans remained vague and his future uncertain. The family lived frugally and managed to get by on a limited income. His cousin reported that Whistler at that time was "slight, with a pensive, delicate face, shaded by soft brown curls…he had a somewhat foreign appearance and manner, which, aided by natural abilities, made him very charming, even at that age."

West Point

Whistler was sent to Christ Church Hall School with his mother's hopes that he would become a minister. Whistler was seldom without his sketchbook and was popular with his classmates for his caricatures. However, after it became clear that a career in religion did not suit him, he applied to the United States Military Academy at West Point, where his father had once taught drawing, and other relatives had attended. On the strength of his family name, and despite his extreme nearsightedness and poor health history, he was admitted to the highly selective institution. However, during his three years there, his grades were barely satisfactory, and he was a sorry sight at drill and dress. Known as "Curly" for his hair length which exceeded regulations, Whistler bucked authority, spouted sarcastic comments, and racked up demerits. His major accomplishment was learning drawing and mapmaking from American artist Robert W. Weir.

His departure from West Point seems to have been precipitated by a failure in a chemistry exam where, when asked to describe silicon began by saying "Silicon is a gas." As he himself put it later: "If silicon were a gas, I would have been a general one day." However, a separate anecdote suggests misconduct in drawing class as the reason for Whistler's departure.

First job

After West Point, Whistler worked as draftsman mapping the entire U.S. coast for military and maritime purposes. He found the work boring and he was frequently late or absent. He spent much of his free time playing billiards and idling about, was always broke, and though a charmer, had little acquaintance with women. After it was discovered that he was drawing sea serpents, mermaids, and whales on the margins of the maps, he was transferred to the etching division of the U. S. Coast Survey. Though he lasted there only two months, he learned etching technique which later proved valuable to his career.

At this point, Whistler firmly decided that art would be his future. For a few months he lived in Baltimore with wealthy friend Tom Winans, who even furnished Whistler with a studio and some spending cash. The young artist made some valuable contacts in the art community and also sold some early paintings to Winans. Whistler turned down his mother's suggestions for other more practical careers and informed her that with money from Winans, he was setting out to further his art training in Paris. Whistler would never return to the United States.

Art study in France

Whistler arrived in Paris in 1855, rented a studio in the Latin Quarter, and quickly adopted the life of a bohemian artist. Soon, he had a French girlfriend, a dressmaker named Heloise. He studied traditional art methods for a short time at the Ecole Imperiale and at the atelier of Charles Gabriel Gleyre. The latter was a great advocate of the work of Ingres, and impressed Whistler with two principles that he used for the rest of his career: line is more important than color and that black is the fundamental color of tonal harmony. Twenty years later, the Impressionists would largely overthrow this philosophy, banning black and brown as "forbidden colors" and emphasizing color over form.

Whistler preferred self-study (including copying at the Louvre) and enjoying the cafe life. While letters from home reported his mother's efforts at economy, Whistler spent freely, sold little or nothing in his first year in Paris, and was in steady debt. To relieve the situation, he took to painting and selling copies he made at the Louvre and finally moved to cheaper quarters. As luck would have it, the arrival in Paris of George Lucas, another rich friend, helped stabilize Whistler's finances for awhile. In spite of a financial respite, the winter of 1857 was a difficult one for Whistler. His poor health, made worse by excessive smoking and drinking, laid him low.

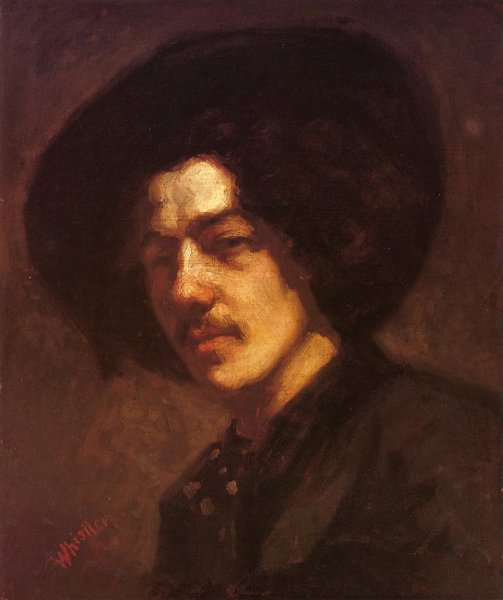

Conditions improved during the summer of 1858. Whistler recovered and traveled with fellow artist Ernest Delannoy through France and the Rhineland. He later produced a group of etchings known as "The French Set", with the help of French master printer Auguste Delâtre. During that year, he painted his first self-portrait, "Portrait of Whistler with Hat", a dark and thickly rendered work reminiscent of Rembrandt. But the event of greatest consequence that year was his friendship with Henri Fantin-Latour, whom he met at the Louvre. Through him, Whistler was introduced to the circle of Gustave Courbet, which included Carolus-Duran (later the teacher of John Singer Sargent), Alphonse Legros, and Edouard Manet.

Also in this group was Charles Baudelaire, whose ideas and theories of "modern" art influenced Whistler. Baudelaire challenged artists to scrutinize the brutality of life and nature and portray it faithfully, avoiding the old themes of mythology and allegory. Theophile Gautier, one of the first to explore translational qualities among art and music, may have inspired Whistler to view art in musical terms.

London

Reflecting the banner of realism of his adopted circle, Whistler painted his first exhibited work, La Mere Gerard in 1858. He followed it by painting At the Piano in 1859 in London, which he adopted as his home, while also regularly visiting friends in France. At the Piano is a portrait done of his niece and her mother in their London music room, an effort which clearly displayed his talent and promise. A critic wrote, "[despite] a recklessly bold manner and sketchiness of the wildest and roughest kind, [it has] a genuine feeling for colour and a splendid power of composition and design, which evince a just appreciation of nature very rare amongst artists." The work is unsentimental and effectively contrasts the mother in black and the daughter in white, with other colors kept restrained in the manner advised by his teacher Gleyre. It was displayed at the Royal Academy the following year, and in many exhibits to come.

In a second painting done in the same room, Whistler demonstrated his natural inclination toward innovation and novelty by fashioning a genre scene with unusual composition and foreshortening. It was later re-titled Harmony in Green and Rose: The Music Room. This painting also demonstrated Whistler's ongoing work pattern, especially with portraits: a quick start, major adjustments, a period of neglect, then a final flurry to the finish. After a year in London, as counterpoint to his 1858 French set, in 1860, he produced another set of etchings called Thames Set, as well as some early impressionistic work, including The Thames in Ice. At this stage, he was beginning to establish his technique of tonal harmony based on a limited, pre-determined palette.

Early career

In 1861, after returning to Paris for a time, Whistler painted his first famous work, Symphony in White, No. 1: The White Girl. The portrait of his mistress and business manager Joanna Hiffernan was created as a simple study in white; however, others saw it differently. The critic Jules Castagnary thought the painting an allegory of a new bride's lost innocence. Others linked it to Wilkie Collins' The Woman in White, a popular novel of the time, or various other literary sources. In England, some considered it a painting in the Pre-Raphaelite manner. In the painting, Hiffernan holds a lily in her left hand and stands upon a bear skin rug (interpreted by some to represent masculinity and lust) with the bear's head staring menacingly at the viewer. The portrait was refused for exhibition at the conservative Royal Academy but in 1863 it was accepted at the Salon des Refuses in Paris, an event sponsored by Emperor Napoleon III for the exhibition of works rejected from the Salon.

Whistler's painting was widely noticed though upstaged by Manet's more shocking painting Le Dejeuner sur l'herbe. Countering criticism by traditionalists, Whistler's supporters insisted that the painting was "an apparition with a spiritual content" and that it epitomized his theory that art should essentially be concerned with the arrangement of colors in harmony, not with a literal portrayal of the natural world.

Two years later, Whistler painted another portrait of Hiffernan in white, this time displaying his new found interest in Asian motifs, which he titled The Little White Girl. His Lady of the Land Lijsen and The Golden Screen, both completed in 1864, again portray his mistress, in even more emphatic Asian dress and surroundings. During this period Whistler became close to Courbet, the early leader of the French realist school, but when Hiffernan modeled in the nude for Courbet, Whistler became enraged and his relationship with Hiffernan began to fall apart. In January 1864, Whistler's very religious and very proper mother arrived in London, upsetting her son's bohemian existence and temporarily exacerbating family tensions. As he wrote to Henri Fantin-Latour, "General upheaval!! I had to empty my house and purify it from cellar to eaves." He also immediately moved Hiffernan to another location

Mature career

In 1866, Whistler decided to visit Valparaiso, Chile, a journey that has puzzled scholars, though Whistler stated that he did it for political reasons. Chile was at war with Spain and perhaps Whistler thought it a heroic struggle of a small nation against a larger one, but no evidence supports that theory. What the journey did produce was Whistler's first three nocturnal paintings-which he termed "moonlights" and later re-titled as "nocturnes"-night scenes of the harbor painted with a blue or light green palette. After he returned to London, he painted several more nocturnes over the next ten years, many of the Thames River and of Cremorne Gardens, a pleasure park famous for its frequent fireworks displays, which presented a novel challenge to paint. In his maritime nocturnes, Whistler used highly thinned paint as a ground with lightly flicked color to suggest ships, lights, and shore line. Some of the Thames paintings also show compositional and thematic similarities with the Japanese prints of Hiroshige. In 1872, Whistler credited his patron Frederick Leyland, an amateur musician devoted to Chopin, for the musically-inspired titles.

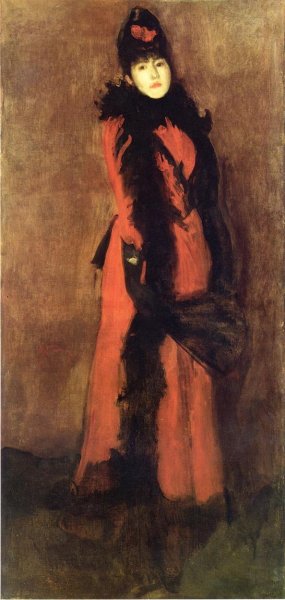

At that point, Whistler painted another self portrait and titled it Arrangement in Gray: Portrait of the Painter (c. 1872), and he also began to re-title many of his earlier works using terms associated with music, such as a "nocturne", "symphony", "harmony", "study" or "arrangement", to emphasize the tonal qualities and the composition and to de-emphasize the narrative content. Whistler's nocturnes were among his most innovative works. Furthermore, his submission of several nocturnes to art dealer Paul Durand-Ruel after the Franco-Prussian War gave Whistler the opportunity to explain his evolving "theory in art" to artists, buyers and critics in France. His good friend Fantin-Latour, growing more reactionary in his opinions, especially in his negativity concerning the emerging Impressionist school, found Whistler's new works surprising and confounding. Fantin-Latour admitted, "I don't understand anything there; it's bizarre how one changes. I don't recognize him anymore." Their relationship was nearly at an end by then but they continued to share opinions in occasional correspondence. When Degas invited Whistler to exhibit with the first show by the Impressionists in 1874, Whistler turned down the invitation, as did Manet, and some scholars attributed this in part to Fantin-Latour's influence on both men.

Portraits

The Franco-Prussian War of 1870 fragmented the French art community. Many artists took refuge in England joining Whistler, including Pissarro and Monet, while Manet and Degas stayed in France. Like Whistler, Monet and Pissarro both focused their efforts on views of the city, and it is likely that Whistler was exposed to the evolution of Impressionism founded by these artists and that they had seen his nocturnes. Whistler was drifting away from Courbet's "damned realism" and their friendship had wilted, as had his liaison with Jo.

Whistler's Mother

By 1871, Whistler returned to portraits and soon produced his most famous painting, the nearly monochromatic full-length figure titled Arrangement in Gray and Black: Portrait of the Artist's Mother, but usually referred to as Whistler's Mother. According to a letter from his mother, one day after a model failed to appear, Whistler turned to his mother and suggested he do her portrait. In his typically slow and experimental way, at first he had her stand but that proved too tiring so the famous profile pose was adopted. It took dozens of sittings to complete.

The austere portrait in his normally constrained palette is another Whistler exercise in tonal harmony and composition. The deceptively simple design is in fact a balancing act of differing shapes, particularly rectangles of the curtain, picture on the wall, wall and floor which stabilize the curve of her face, dress, and chair. Again, though his mother is the subject, Whistler commented that the narrative was of little importance. In reality, however, it was a homage to his pious mother. After the initial shock of her moving in with her son, she aided him considerably by stabilizing his behavior somewhat, tending to his domestic needs, and providing an aura of conservative respectability that helped win over patrons.

Mostly due to its anti-Victorian simplicity during a time in England when sentimentality and fussy decoration were in vogue, the public reacted negatively. Critics thought the painting a failed "experiment" rather than art. The Royal Academy rejected it, then grudgingly accepted it after lobbying by Sir William Boxall-but then hung the painting in an unfavorable location at its exhibition.

From the start, Whistler's Mother sparked varying reactions, including parody, ridicule, and reverence, which have continued to today. While some saw it as "the dignified feeling of old ladyhood", "a grave sentiment of mourning", or a "perfect symbol of motherhood", others employed it as a fitting vehicle for mockery. It has been satirized in endless variation in greeting cards and magazines, and by cartoon characters such as Donald Duck and Bullwinkle the Moose. Whistler did his part in promoting the picture and popularizing the image. He frequently exhibited it and authorized the early reproductions that made their way into thousands of homes.

The painting narrowly escaped being burnt in a fire aboard a train during shipping. Later the painting was purchased by the French government, the first Whistler work in a public collection, and is now housed in the Musee d'Orsay in Paris. During the Depression, the picture was billed as "million dollar" painting and was a big hit at the Chicago World's Fair. It was accepted as a universal icon of motherhood by the world-wide public, which was not particularly aware or concerned with Whistler's aesthetic theories. In public recognition of its status and popularity, the United States issued a postage stamp in 1934 featuring an adaptation of the painting.

Later Years

After the trial, Whistler received a commission to do twelve etchings in Venice. He eagerly accepted the assignment, and with girlfriend Maud arrived in the city, taking rooms in a dilapidated palazzo they shared with other artists, including John Singer Sargent. Though homesick for London, he adapted to Venice and set about discovering its character. He did his best to distract himself from the gloom of his financial affairs and the pending sale of all his goods at Sotheby's. He was a regular guest at parties at the American consulate, and with his usual wit, enchanted the guests with verbal flourishes such as "the artist's only positive virtue is idleness-and there are so few who are gifted at it."

His new friends reported, on the contrary, that Whistler rose early and put in a full day of effort. He wrote to a friend, "I have learned to know Venice in Venice that the others never seem to have perceived, and which, if I bring back with me as I propose, will far more than compensate for all annoyances delays & vexations of spirit." The three month assignment stretched to fourteen months. During this exceptionally productive period, Whistler finished over fifty etchings, several nocturnes, some watercolors, and over 100 pastels-illustrating both the moods of Venice and its fine architectural details. Furthermore, Whistler influenced the American art community in Venice, especially Frank Duveneck and Robert Blum who emulated Whistler's vision of city and later spread his methods and influence back to America.

Back in London, the pastels sold particularly well and he quipped, "They are not as good as I supposed. They are selling!" He was actively engaged in exhibiting his other work but with limited success. Though still struggling financially, however, he was heartened by the attention and admiration he received from the young generation of English and American painters who made him their idol and eagerly adopted the title of "pupil of Whistler". Many of them returned to America and spread tales of Whistler's provocative egotism, sharp wit, and aesthetic pronouncements-establishing the legend of Whistler, much to his great satisfaction.

Whistler published his first book, Ten O'clock Lecture in 1885, a major expression of his belief in "art for art's sake". At the time, the opposing Victorian notion reigned, namely, that art, and indeed much human activity, had a moral or social function. But to Whistler, art was its own end and the artist's responsibility was not to society but to himself, to interpret through art, and to neither reproduce nor moralize what he saw. Furthermore, he stated, "Nature is very rarely right", and must be improved upon by the artist, with his own vision.

With his relationship with Maud unraveling, Whistler suddenly proposed and married Beatrice ("Trixie") Godwin, a former pupil and the former wife of his architect, who had died two years earlier. Her respectability and connections helped bring him badly needed commissions in the early 1890's. His new book, The Gentle Art of Making Enemies, was published in 1890 to mixed success but it afforded helpful publicity.

In 1890, he met Charles Lang Freer, who became a valuable patron in America, and ultimately, his most important collector. Around this time, in addition to portraiture, Whistler experimented with early color photography and with lithography, creating a series featuring London architecture and the human figure, mostly female nudes. In 1891, with help from his close friend Stephane Mallarme, Whistler's Mother was purchased by the French government for 4,000 francs. This was much less than what an American collector might have paid, but that would not have been as prestigious by Whistler's reckoning.

After an indifferent reception to his one-man show in London, featuring mostly his nocturnes, Whistler abruptly decided he had had enough of London. He and Trixie moved to Paris in 1892. He felt welcomed by Monet, Auguste Rodin, Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, and by Stephane Mallarme, and he set himself up a large studio. He was at the top of his career when it was discovered that Trixie had incurable cancer. She died in 1896.

In the final seven years of his life, Whistler did some minimalist seascapes in watercolor and a final self-portrait in oil. He corresponded with his many friends and colleagues. Whistler founded an art school in 1898, but his poor health and infrequent appearances led to its closure in 1901. He died in London on July 17, 1903.

Whistler was the subject of a contemporaneous biography by his friend, the printmaker Joseph Pennell who collaborated with his wife Elizabeth Robins Pennell to write The Life of James McNeill Whistler, published in 1908. The Pennells' vast collection of Whistler material was bequeathed to the Library of Congress. The artist's entire estate was left to his sister-in-law Rosalind Birnie Philip. She spent her life defending his reputation and managing his art and effects, much of which was eventually donated to Glasgow University. (From Wikipedia)